Wilson, North Carolina’s story has captivated the imagination of the country. Farm machinery repairman, Vollis Simpson, began making gigantic kinetic sculptures at his family farm in Wilson County when he was nearing retirement age. He kept making his “whirligigs”–seven days a week–until about six months before he died at the age of 94 in May of 2013. By that time he was famous. The story of Wilson’s campaign to use the renowned whirligigs to recharge its downtown has catapulted the community into the national spotlight. Grants from ArtPlace America, the Kresge Foundation, and the National Endowment for the Arts have helped the project come close to its goal of opening the Vollis Simpson Whirligig Park and Museum.

The field of these “whirligigs” was 11 miles outside the City of Wilson and already attracted the attention of local people. After the rise of the Internet, visitors from out-of-state made their way to Vollis’ farm too. Without any advertising, Simpson’s farm became one of Wilson County’s top tourism destinations. His work began to be discovered by art collectors. At the American Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland you will find his 55-foot-tall, 45-foot-wide “Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness” on permanent display. His works are part of several other collections, including the American Folk Art Museum in Manhattan and once featured in a popular window installation at New York’s Bergdorf Goodman department store.

As Simpson’s health declined he wasn’t able to grease or paint the 40′-50′ tall sculptures that were made from recycled industrial parts and endured rain, sun, and hurricanes for thirty years. It became clear that without intervention, Wilson’s number one attraction would soon disappear. In 2010, a plan was announced to create the Vollis Simpson Whirligig Park in Historic Downtown Wilson. Simpson was delighted that his work would survive and continue to delight people for generations to come. He was assisting in the effort to relocate the whirligigs to a downtown warehouse where they are being restored, rebuilt in some cases, and repainted. By the time the park is complete, 30 whirligigs, some standing 50 feet tall or more, will be transported, restored and installed.

Fortunately a lot of people in Wilson (and all over the world) love Vollis Simpson’s whirligigs. They banded together to save them. Their plan is to rescue the whirligigs and the city at the same time–the whole package.

In the process, Wilson became a national model for creative placemaking. Cities all over the Untied States are rallying around their best arts assets to create the hearts of large and small cities. Here’s how the National Endowment for the Arts describes it:

In creative placemaking, partners from public, private, nonprofit, and community sectors strategically shape the physical and social character of a neighborhood, town, tribe, city, or region around arts and cultural activities. Creative placemaking animates public and private spaces, rejuvenates structure and streetscapes, improves business viability and public safety, and brings diverse people together to celebrate, inspire, and be inspired.

– Markusen and Gadwan, Creative Placemaking Report

By leveraging one of Wilson’s most unique cultural assets into an economic engine of entrepreneurial job creation and tourism, the Wilson community will add vibrancy to its Historic Downtown.

Vollis Simpson Whirligig Park and Museum is part of a public/private partnership that includes City of Wilson, Wilson Downtown Properties, Wilson Downtown Development Corporation, and others. A massive effort is underway to document, repair, and conserve the whirligigs, which have suffered from nearly 30 years of exposure to the elements. Add to that the fact that they were all originally constructed of recycled and salvaged parts, throw in a few hurricanes and summer humidity, and you have a perfect storm of conservation needs. Fortunately, the project has the advice of respected conservator Ron Harvey. Juan Logan, retired UNC Chapel Hill professor and acclaimed artist. Dennis Montagna from the National Parks Service, and others from the Smithsonian Institution, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), and DuPont, we well as a National Advisory Board. New protocols for conservation of outdoor folk art and vernacular artist environments have been established through this project’s pioneering process.

In 2016 the Kohler Foundation became a partner in the project, which allowed for the completion of the conservation efforts.

Vollis Simpson never called himself an artist, but the New York Times did. Upon his death in 2013, the Times described Simpson as “a visionary artist of the junkyard…who made metal scraps into magnificent things that twirled and jangled and clattered when he set them out on his land.”

Simpson’s monumental, fanciful, wind-driven creations-popularly called “whirligigs” – have been appreciated by millions of people in art museums and other venues. In 2013 they were named North Carolina’s official folk art.

Simpson’s monumental, fanciful, wind-driven creations-popularly called “whirligigs” – have been appreciated by millions of people in art museums and other venues. In 2013 they were named North Carolina’s official folk art.

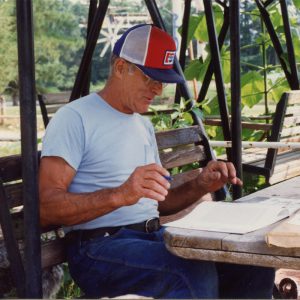

Simpson’s fame came near the end of his life. He was born in 1919 to a farming family with 12 children. As a boy, he helped his father supplement the family income by moving houses. This somewhat unusual occupation called upon age-old techniques of fulcrum, leverage and rollers, and the Simpson side business spanned the years of horse power transitioning to automotive power.

He served in the Army Air Corps during WWII with duty on the South Pacific island of Saipan. The isolated troops struggled to keep uniforms clean so Simpson experimented with rudimentary windmill technology using a junked B-29 bomber to power a large washing machine.

After the war, Simpson partnered with several friends to open a machinery repair shop. As the years passed, Simpson followed in his father’s footsteps and developed a house-moving side to the business. During both jobs, he began to collect odd machinery parts, industrial salvage, transportation supplies, and other useful objects that he didn’t want to go to waste.

After retiring at 65, he started tinkering around with his collection of odd parts. Using some of the same rigs he’d developed for moving houses, Simpson began constructing enormous windmills in his yard. They did not resemble the working windmills of grinding or irrigation use, but referenced the concepts of weather vanes and handcrafted whirligigs that are still seen locally on houses, fence posts and barns.

The field of these “whirligigs” soon began attracting the attention of local people, and after the rise of the Internet, visitors from out-of-state. Without any official advertising, Simpson’s farm became one of Wilson County’s top tourism destinations.

The Whirligigs incorporate highway and road signs, HVAC fans, bicycles, ceiling fans, mirrors, stovepipes, I-beams, pipe, textile mill rollers, ball bearings, aluminum sheeting, various woods, steel rods, rings, pans, milkshake mixers and many more such materials form the support and moving parts.

Simpson cut decrepit road signs into one-inch and larger squares so that the whirligigs would be reflective at night.

Images inside the whirligigs are farm animals and people; references to Simpson’s experiences, such as the many WWII era airplanes; lumberjacks sawing wood; and a guitar player based on Simpson’s son.

In 2010, a plan was announced to create the Vollis Simpson Whirligig Park in Historic Downtown Wilson. Simpson died in 2013 at 94, but not before seeing the first of his creations installed in the park that bears his name.

The Vollis Simpson Whirligig Park was originally conceived with the input of hundreds of Wilson citizens including downtown stakeholders, artists, youth groups, neighborhood associations, and business leaders. Through multiple community meetings, Wilsonians helped contribute to the design and vision for the park. As the project progressed, a workforce training program was developed and implemented in partnership with Wilson Community College, Opportunities Industrialization Center of Wilson, and St. John’s Community Development Corporation for whirligig repair and conservation. Over fifty jobs were created throughout the course of the whirligig restoration effort.

Based on designed by award-inning landscape architecture firm Surface678, the two-acre park features thirty of Vollis Simpson’s whirligigs. This is the largest collection in the world and includes some of Simpson’s most colossal and impressive sculptures. The Green, a central grass amphitheater, is a reference to the pond on the Simpson farm, with the surrounding whirligigs installed as they originally were around the body of water. This space, which includes a stage, was created to host various concerts and performances. Mimicking rows of crops in the fields and long lines of tobacco ready for auction in the warehouses, the rows of concrete and garden squares in the park pay homage to Wilson’s agricultural heritage.

The Pavilion, a large, open-air shelter, was created to house downtown arts, crafts and farmers markets, as well as other community events and activities. The pavilion, designed by Hood & Herring Architecture, echoes surrounding tobacco auction warehouses. Specialty night lighting illuminates the thousands of reflectors attached to the whirligigs, recreating the mystical experience at the original location when car headlights rounded the curve near the Simpson farm. If you have any questions about the park please reach out to our Whirligig Park Events Manager at 252-360-4150 or Museum staff, at 252-674-1352.